Lead Author:

Ethan Bucholz, PhD, Academic Liaison and Experiential Learning Specialist, Colorado State Forest Service

Contributing Authors:

Amanda West Fordham, PhD, Associate Director of Science and Data, Colorado State Forest Service

Linda Nagel, PhD, Department Head of Forest and Rangeland Stewardship, Warner College of Natural Resources, Colorado State University

Courtney Peterson, Research Associate III, Warner College of Natural Resources, Colorado State University

The challenges presented by climate change to Colorado forests necessitate forward thinking from forest managers. Terms once uncommon in the forestry lexicon are now more widely used. We will discuss three climate adaptation concepts in this post: resistance, resilience and transition.

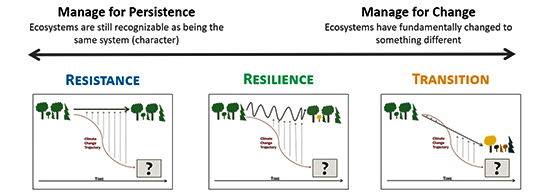

Often, we use these terms interchangeably or in conjunction given their conceptual links, but we intend to provide a look at some of the nuance behind their usage. It is important to remember that these terms represent a spectrum of options, from maintaining relatively unchanged conditions to actively promoting adaptive responses within a given system, and there exists considerable overlap in tactics and actions while they differ in intent. Considerations of forested ecosystems in their current condition, as well as the development of desired future conditions, can provide insight on how to differentiate these terms and use them properly. Further, resistance, resilience and transition provide a framework toward explicitly including uncertainty with climate change during forest management planning, through considering different adaptation strategies, approaches and tactics.

Important Definitions

Resistance, resilience and transition (sensu Nagel et al. 2017; Swanston et al. 2016; Millar et al. 2007) represent a spectrum of approaches to forest management, both in the short- and long-term (Figure 1). Resistance, within this framework, is defined as “actions that improve the defenses of the forest against anticipated change, or directly defend the forest against disturbance to maintain relatively unchanged conditions.” Resilience is defined as “actions that accommodate some degree of change, but encourage a return to a prior condition or desired reference conditions after disturbance.” Transition is defined as “actions that intentionally accommodate change and enable ecosystems to adaptively respond to changing and new conditions.”

While these definitions provide some clarity toward differentiating resistance, resilience and transition, note that development of desired future conditions for a given management parcel will help land managers formulate strategies and integrate these concepts to design goals, objectives and evaluation criteria to meet those desired conditions. Desired future conditions, as indicated in GTR-373 (see Addington et al. 2018), describe the expected spatial arrangement of forest vegetation and how this varies across scales (landscape to operational) to achieve and maintain values and identified ecological processes. This is an important part of the planning phase and determining both how a given management parcel fits into larger spatial contexts, while also providing context for determining how to use resistance, resilience and transition to meet project goals and desired conditions.

Exploring Resistance, Resilience and Transition

For any forest management project, working with landowners begins with defining goals for the management of a specific parcel. Considering landowner goals, identifying ecological processes and developing desired conditions is an important first step. From these goals and desired conditions, we develop objectives and evaluation criteria, which serve as baselines upon which outcomes of particular actions can be measured. Integrating climate-adaptive concepts such as resistance, resilience and transition becomes an important part of this process, as it specifies general strategies and approaches that may be taken in the near-term to encourage long-term benefits in the face of a rapidly changing climate. What are the general outcomes for a management parcel? Will it be the same after management actions? What ecological processes and services are we attempting to foster with management activities?

A legacy Douglas-fir grows within a mixed-conifer forest in southwest Colorado. Photo courtesy of Tim Leishman, U.S. Forest Service, San Juan National Forest[/caption]

To look at these concepts, we will use lower montane forests to elucidate subtle differences in each approach. Imagine an overstocked ponderosa pine forest, with canopy closure and abundant ladder fuels, but dominated by mature pine in the overstory. What values are at risk in this stand? What disturbances threaten stand continuity? Answers may be along the lines of drought mortality, insect activity and stand-replacing (or severe) wildfire risks, which pose a threat to water filtration, erosion and sedimentation, protection of threatened/endangered species and loss of place, amongst other values.

If desired conditions include maintaining the current conditions, the management actions we take are toward this system being able to resist change (i.e. resistance). Management actions are numerous, but could involve reducing stand density to decrease intraspecific (within species) competition and drought stress; reducing insect activity by maintaining densities below or outside of stand density indices that promote insect population growth; promoting openings and open-canopy conditions, while removing ladder fuels to lessen chances for canopy fire; and maintaining refugia (i.e. locations that allow shrinking populations of species to persist) for threatened or endangered species. Forest managers can integrate desired future conditions focused on improving the defenses of the lower montane forest system against change into their development of management objectives and outcomes. However, these actions will be transient, temporally, as the resulting openings will eventually in-fill with vegetation in the absence of routine disturbance. Maintaining this in perpetuity will require intervention to maintain it in the future.

Resilience considerations within this same stand could look very similar to those described above, with a different focus on the system’s ability to respond to disturbance. This may include maintaining mature, seed-bearing and older trees as individuals, varying numbers within groups of trees, increasing spatial heterogeneity of openings and groups across the stand, allowing managed wildfires to burn in treated stands, and promoting species that respond well to disturbance. Moving from resistance to resilience, we shift focus away from maintaining the current system to withstanding and responding to negative impacts of disturbances.

For transition, this is where we intentionally focus on promoting adaptive responses and facilitating change. We will shift away from the aforementioned ponderosa pine stand to highlight some synergies with other topics like restoration. Restoration focuses primarily on degraded ecosystems, wherein management changes/alterations to characteristic disturbances have resulted in conditions that would not be historically present. Note that not all restoration activities require transition.

Mostly homogenous and closed-canopy stand conditions, such as these from southwest Colorado, provide conditions that support regeneration of shade tolerant species such as white fir, while offering opportunities for forest management to build age class and structural diversity to better prepare these forests for climate change. Photo courtesy of Tim Leishman, U.S. Forest Service, San Juan National Forest[/caption]

For our hypothetical stand, we are going to look at a forest with some ponderosa pine in the overstory, but mostly Douglas-fir and white fir in both the overstory and understory. The concept of transition is useful here because the current stand conditions are reflective of past management or absence of disturbance, but the desired stand, when considering climate change projections, will be different from current. We are therefore looking to transition this stand, which may mean complete removal of non-pine overstory and understory, and creating large patch openings that we replant with ponderosa pine or place strategically around existing mature pine. This will move the system toward compositions that are both drought tolerant and fire-resistant.

This is also an area of viewing these actions on multiple time scales, as the short-term goals promote transition to a different species composition and structure, but longer-term, with the transition today, the stand will be more resistant to disturbances farther into the future. The time scale is an important consideration, as well as indicating to the landowner the intention to transition their stand away from shade tolerant conifers and move it toward shade intolerant conifers or disturbance-loving compositions that may be able to cope with future climate. Proactively, foresters can move a given parcel toward a different system state wherein the structures created and species planted reflect an intentional effort to transition areas toward species that will be better adapted for the future.

As climate continues to change, considering innovative tactics to manage Colorado forests will become more important. Resistance, resilience and transition represent an emerging lexicon that integrates current conditions with desired future conditions, thereby guiding management actions. Knowing and understanding the differences between these terms will prove useful as we continue to recommend management strategies to different ownerships and collaborative groups.

Footnotes

Addington, R. N., Aplet, G. H., Battaglia, M. A., Briggs, J. S., Brown, P. M., Cheng, A. S., Dickinson, Y., Feinstein, J. A., Pelz, K. A., Regan, C. M., Thinnes, J., Truex, R., Fornwalt, P. J., Gannon, B., Julian, C. W., Underhill, J. L., & Wolk, B. (2018). Principles and practices for the restoration of ponderosa pine and dry mixed-conifer forests of the Colorado Front Range. RMRS-GTR-373. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 121 p.

Millar, C. I., Stephenson, N. L., & Stephens, S. L. (2007). Climate change and forests of the future: Managing in the face of uncertainty. Ecological Applications, 17(8), 2145-2151.

Nagel, L. M., Palik, B. J., Battaglia, M. A., Amato, A. W. D., Guldin, J. M., Swanston, C. W., Janowiak, M. K., Powers, M. P., Joyce, L. A., Millar, C. I., Peterson, D. L., Ganio, L. M., Kirschbaum, C., & Roske, M. R. (2017). Adaptive Silviculture for Climate Change: A National Experiment in Manager-Scientist Partnerships to Apply an Adaptation Framework. Journal of Forestry, 115(3), 167-178.

Swanston, C. W., Janowiak, M. K., Brandt, L. A., Butler, P. R., Handler, S. D., Shannon, P. D., Lewis, A. D., Hall, K., Fahey, R. T., Scott, L., Kerber, A., Miesbauer, J. W., Darling, L., Parker, L., & St. Pierre, M. (2016). Forest Adaptation Resources: Climate Change Tools and Approaches for Managers, 2nd Edition. NRS-GTR-87-2. Newtown Square, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station, 170 p.