Analyzing Merchantable Net Volume by Common Disturbances Utilizing FIA Data and EVALIDator

Authors:

- Montgomery Reese, Research Associate II, Colorado State Forest Service

- Jim Jones, FIA Forester (Retired), Colorado State Forest Service

Editors:

- Sara Goeking, FIA Deputy Program Manager, USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station

- Wilfred Previant, PhD, Assistant Professor, Warner College of Natural Resources, Colorado State University

- Amanda West Fordham, PhD, Associate Director of Science and Data, Colorado State Forest Service

The Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) program of the USDA Forest Service (USFS) has been in continuous operation since 1930. In Colorado and Wyoming, the USFS collaborates with the Colorado State Forest Service (CSFS) to conduct and continuously update a comprehensive inventory of forest conditions in the two states.

The FIA program annually surveys 10 percent of thousands of permanent plots in each state. Each plot represents 6,000 acres of land across all ownerships. The inventory includes information about trees, seedlings, saplings, shrubs, forbs, grasses, down woody material and soils. Additional information including lynx habitat, lichens and root diseases is sometimes collected.

Scientists from the USFS Rocky Mountain Research Station analyze FIA plot data. They produce reports every five years on the health of Colorado’s forests, along with a wide range of other scientific studies. These data are available to the public online for analysis of Colorado’s and other state’s forests.

The FIA data can be analyzed using tools such as EVALIDator and DATIM, found on the USFS FIA website. These tools are public domain, used by scientists, land managers, corporations and individuals. For this analysis, EVALIDator was used to analyze disturbances in forested land in Colorado from 2010 to 2019.

Most Common Disturbances

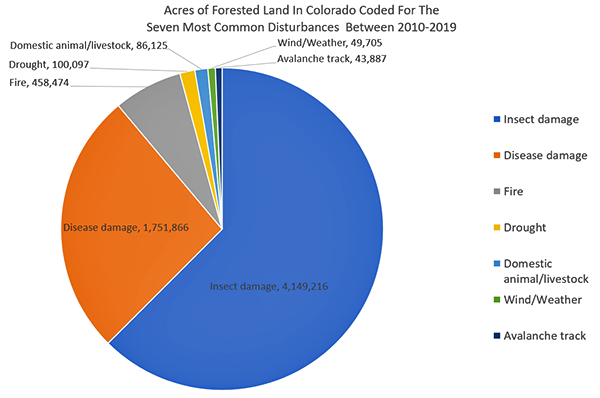

A disturbance can be natural or human-caused. It has to be at least 1 acre in size and affect at least 25 percent of the forest canopy to be recorded in the field. Although FIA crews typically record specific types of disturbances (e.g., crown vs. ground), these disturbances have been aggregated to simplify this graph (Figure 1).

Insect damage was by far the most widespread disturbance, affecting over 4.1 million acres. Diseases were the second most commonly recorded disturbance, affecting over 1.7 million acres. Fire affected over 441,000 acres. The other top five disturbances totaled approximately 280,000 acres. There is approximately 24.5 million acres of forest in Colorado and approximately 17.7 million acres of forest had no visible disturbance observed, leaving 6.8 million acres having some observable disturbance.

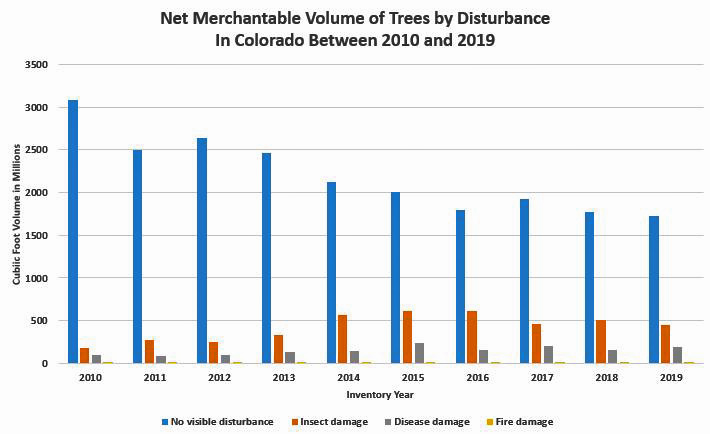

The amount of forests affected by insects and disease, reported in merchantable net volume, increased from 2010 to 2015 in Colorado but has since been declining. Meanwhile, the amount of volume affected by fire damage remains steady from year to year. The majority of volume in Colorado remains unaffected by disturbances (Figure 2).

Exploring Forest Disturbances

The forests in Colorado are subject to many different disturbances. Some of the most common disturbances are insect damage, disease damage and fire damage. Historically, colder winter temperatures helped suppress insect populations (Raffa 2008; Negron and Cain 2019). Climate change has caused warmer winters, leading to beetle populations surviving the winter (Negron and Cain 2019). Climate change has also led to less snowpack, which reduces the amount of water available for the growing season (Negron and Cain 2019; Creeden et al. 2014). Lack of water reduces the amount of resin trees can produce (Negron and Cain 2019). Resin is essential for trees to fend off unwanted insects and survive insect attacks (Negron and Cain 2019).

Tree pathogens can be hard to notice with the naked eye. Diseases can affect trees and not show fruiting bodies, which are the obvious sign of an infection. Sometimes, it requires peeling away the bark of a tree to expose discoloration and mycelial fans (fanlike array of fungus) to know a tree is infected. Insects and diseases are two factors that often result in the mortality of a tree (Lalande 2020). Trees affected by drought may survive, but when coupled with an insect or disease, the chances of survival are far less (Lalande 2020).

Wildfire can play a huge role in the disturbance of forests in Colorado. Lower elevation forests, such as ponderosa pine, are adapted to low-severity fires that are more frequent (Keith et al. 2010). Higher elevation forests, such as lodgepole pine, are adapted to infrequent but higher severity fires (Keith et al. 2010). Figure 2 shows there is less volume affected by fire than is affected by disease and insects.

Sampling Error

Table 1 (below) represents the sampling error percent at a 68 percent confidence level for the data in the bar graph in Figure 2. Sampling error percentage is correlated to the number of plots measured where the type of disturbance was observed.

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| No visible disturbance | 8.12% | 8.37% | 8.51% | 8.97% | 9.04% | 9.05% | 9.8%% | 9.8%% | 10.38% | 9.41% |

| Insect damage | 28.54% | 25.07% | 23.64% | 22.33% | 16.07% | 17.82% | 16.23% | 21.33% | 20.52% | 19.67% |

| Disease damage | 41.98% | 40.8%% | 42.22% | 32.84% | 37.32% | 28.3% | 29.01% | 23.91% | 31.22% | 31.38% |

| Fire damage | 100.48% | 82.77% | 94.1% | 89.01% | 98.57% | 84.4% | 82.8% | 60.8% | 90.23% | 82.81% |

Footnotes

Creeden, Eric P., et al. “Climate, Weather, and Recent Mountain Pine Beetle Outbreaks in the Western United States.” Forest Ecology and Management, vol. 312, 2014, pp. 239–251., doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2013.09.051.

Keith, Robin P., et al. “Understory Vegetation Indicates Historic Fire Regimes in Ponderosa Pine-Dominated Ecosystems in the Colorado Front Range.” Journal of Vegetation Science, vol. 21, no. 3, 2010, pp. 488–499., doi:10.1111/j.1654-1103.2009.01156.x.

Lalande, Bradley M., et al. “Subalpine Fir Mortality in Colorado Is Associated with Stand Density, Warming Climates and Interactions among Fungal Diseases and the Western Balsam Bark Beetle.” Forest Ecology and Management, vol. 466, 2020, p. 118133., doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118133.

Negrón, José F, and Bob Cain. “Mountain Pine Beetle in Colorado: A Story of Changing Forests.” Journal of Forestry, vol. 117, no. 2, 2018, pp. 144–151., doi:10.1093/jofore/fvy032.

Raffa, Kenneth F., et al. “Cross-Scale Drivers of Natural Disturbances Prone to Anthropogenic Amplification: The Dynamics of Bark Beetle Eruptions.” BioScience, vol. 58, no. 6, 2008, pp. 501–517., doi:10.1641/b580607.