Forests and Water United in the West

In a changing climate, our forests need to be resilient in the face of drought, wildfire, insects and diseases to ensure water remains clean and accessible to people, wildlife and the landscape.

Water is the lifeblood of the West. When Coloradans turn on their taps, the water has a surprising origin story – one that starts high in the mountains, filtered through forests. In celebrating UN World Water Day, let’s explore the connection between water and forests here in Colorado and the critical role forests play in protecting this precious resource.

Water in the West

A watershed is an area of land united by the flow of water, nutrients, pollutants and sediments, moving downslope to the lowest point through a network of drainage pathways, either underground or on the surface. Water is key to sustaining life in the environment, but it’s also a product of the land surrounding it.

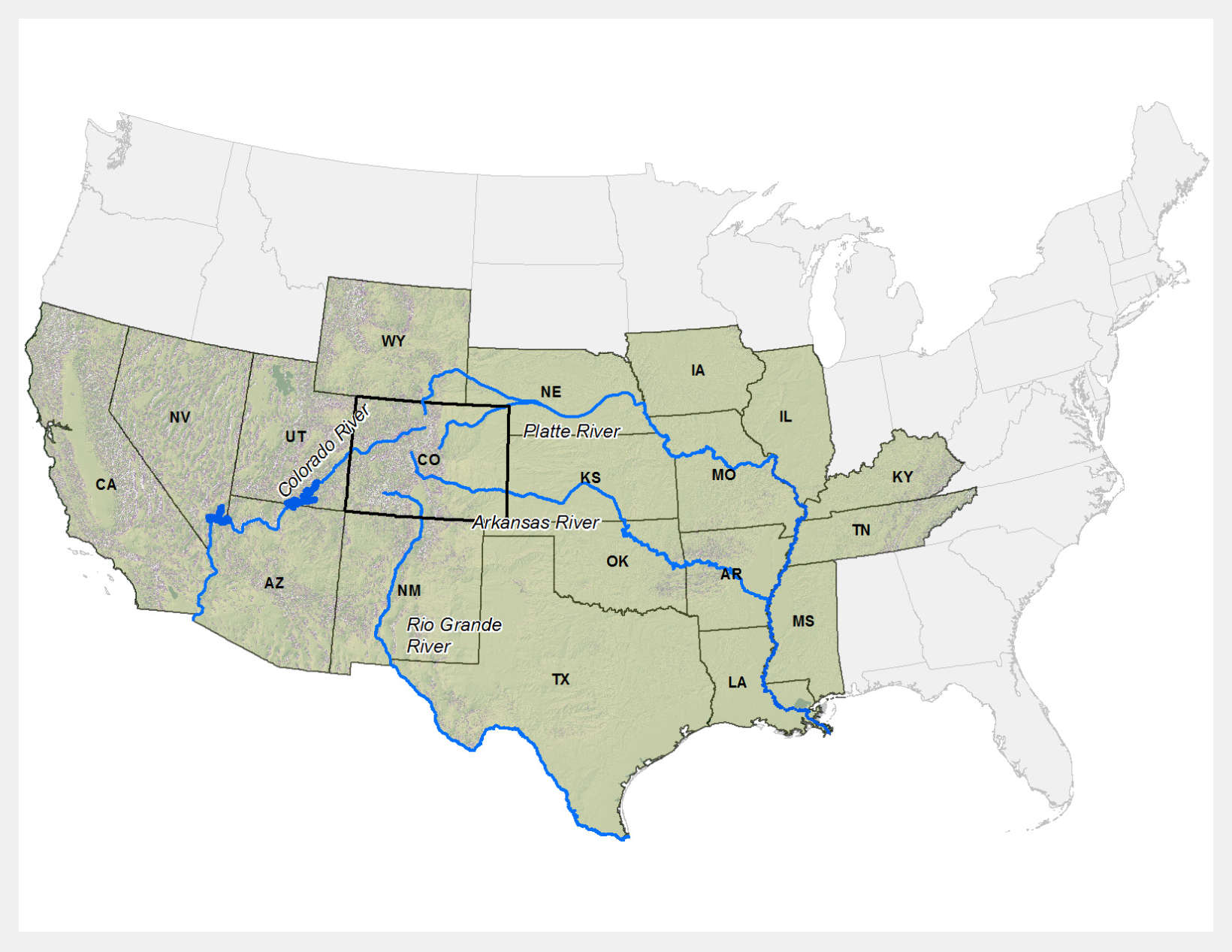

Colorado’s headwaters play a crucial role in meeting our nation’s need for fresh water. The water supply for Colorado and 18 other states comes from our high-country watersheds. Four major river systems – the Platte, Colorado, Arkansas and Rio Grande – originate in Colorado’s mountains and fully drain into one-third of the landmass of the lower 48 states.

Snow from the mountains supplies 75 percent of the water to these river systems. About 40 percent of the water comes from the highest 20 percent of the land, most of which lies in national forests.

Colorado water supports everything from municipalities to farmers and ranchers, and from fisheries to wildlife – with river water typically recycled and reused many times before it ever leaves the state. Colorado’s semi-arid climate, recurring droughts and competing demands for a limited resource make these water supplies even more critical.

Linking Water and Forests

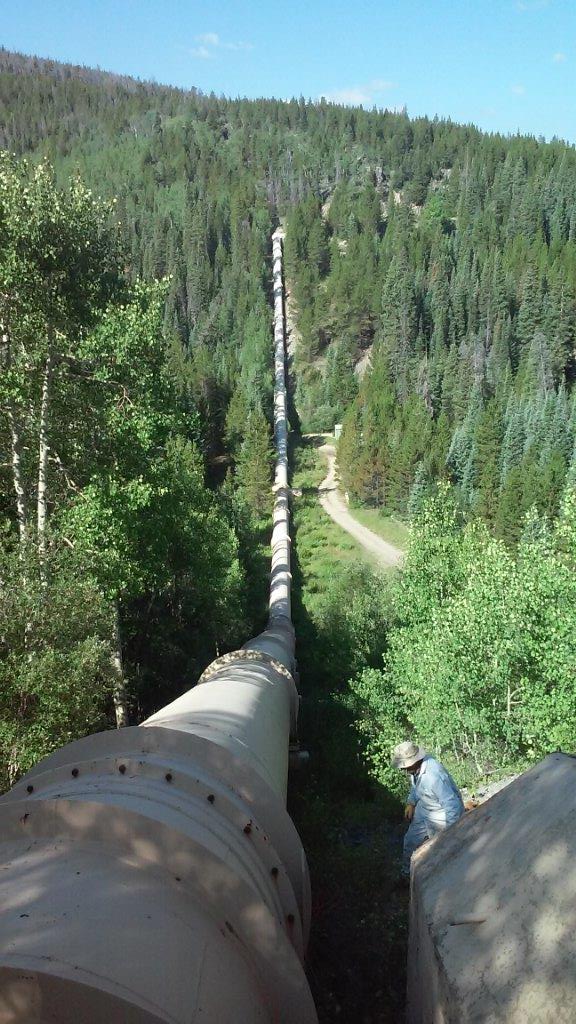

Forests receive precipitation, use it for sustenance and growth, and influence water storage or movement to other parts of the environment. As snow melts in Colorado’s high country, it travels through forests and wetlands. In addition to removing pollutants, forests keep sediment out of water supplies, regulate stream flows, reduce flood damage and store water.

Healthy watersheds provide more than just drinking water, serving as habitat for wildlife and promoting biodiversity. This supports the resiliency of the entire forest, in addition to offering spaces for people to recreate and engage with nature.

Threats to Watersheds and Forests

Promoting healthy and resilient forests is one way to protect watersheds. But Colorado’s forests are vulnerable to a growing number of disturbances that can impact watersheds across Colorado, threatening water quality and availability for millions of Americans.

Almost 40 percent of watersheds in the West are at high risk to wildfire, with 636,000 of those watershed acres here in Colorado. Uncharacteristic wildfire can trigger cascading effects. Areas that burn completely tend to have slower regeneration of trees and other plants, resulting in changes in snowmelt timing and a higher potential for flooding and debris flows that harm water infrastructure.

Insects and diseases can cause a slow but steady change in forests. In areas with beetle-killed trees, wildfires can be more intense and more difficult to suppress.

Growing populations in the wildland-urban interface heighten demand for drinking water and water-intensive agricultural products, spur the need for wildfire mitigation actions, and increase the number of people recreating in Colorado’s forests.

We all live in a watershed and everything we do on our property can have an impact. The land drains into tributaries, streams and creeks that flow into bigger rivers. As this water flows downhill, it picks up debris and sediments that can impact water quality.

Managing Forests to Protect Watersheds

The CSFS helps treat more than 17,000 acres of forestlands, using selective thinning to remove accumulated fuels catered for the needs of a given area. The result is a forest that is more resilient in the face of wildfire, with reduced risk of flooding and sediment movement into watersheds.

CSFS foresters in field offices across Colorado provide direct assistance to landowners. They create forest management plans and advise on the development of Community Wildfire Protection Plans. By working so closely with community groups, foresters can include watershed protection expertise when planning projects.

When insects or diseases leave swaths of standing dead trees, foresters take on fuels reduction projects to remove trees that increase the risk of uncharacteristic wildfire. This also happens in areas that have experienced decades of fire suppression and consequently have dense undergrowth that raises the risk of a high-intensity crown fire.

Collaboration and Future Work

As a headwaters state, actions taken in Colorado affect water security in other states. The Colorado River originates from the high-elevation snowfields in Rocky Mountain National Park and supplies water to 40 million people downstream. Decades of drought combined with higher demands on the water from growing populations have dramatically decreased the amount of water in the river, as well as the reservoirs it feeds. Concerns about water availability are not hypothetical; shortages are already being felt and observed.

Keeping water available is an ongoing process that depends on effective collaboration and constant work with contractors, landowners and partners at the federal, local, private or non-governmental levels.

The Colorado Water Plan is a framework developed to meet the state’s water needs, and it describes a shared stewardship ethic to protect the health of watersheds. Staff at the CSFS consult with partners and other entities to identify priority areas for watershed protection projects. The 2020 Colorado Forest Action Plan identifies key watersheds that affect agriculture, downstream communities, recreation and ecosystem function.

The CSFS is uniquely positioned to lead cross-boundary, watershed-level projects that have large impacts on communities and individuals. Some examples of the agency’s partnerships include the Forests to Faucets program and the Forest and Land Management Services Agreement with Denver Water, which has supported healthy forest practices in Boulder, Clear Creek, Douglas, Eagle, Grand, Jefferson, Park and Summit counties since the mid-1980s.

A Changing Climate

Forest management in a changing climate needs to be responsive to environmental and societal changes to ensure that the state’s forests continue to provide fundamental benefits, while minimizing risks within them.

Reforestation is also critical to keeping our forests resilient and growing. The CSFS nursery grows seedling trees and shrubs, distributing more than 500,000 each year for conservation goals including reforesting burned areas, enhancing wildlife habitat and reducing soil erosion after flooding.

Management approaches that explore multiple possible future conditions, rather than a single outcome, are ideal to manage current climate projections and help forest managers and landowners best prepare for an uncertain future.

The management choices we make now will have long-term implications for Colorado’s residents and forests. This requires careful consideration of what we want our future forests to provide and selecting management options that best achieve those outcomes for the benefit of future generations.